Click here for: Wellness Program l Yoga l Research & Studies

Co-Principal Investigators: George Salem, PhD, Gail A. Greendale, MD

Why did we do this research study?The main reasons we conducted this study were to quantify the physical demands and functional performance adaptations (e.g. changes in strength, balance, etc) of a 32-week yoga program designed for community-dwelling older adults.

The physical demands and functional performance adaptations were assessed using biomechanical investigation (described further below).

Our goal is to use data from the study to develop evidence-based Yoga programs for ambulatory seniors. We hope that evidence-based programs will be associated with fewer musculoskeletal side effects compared to Yoga programs that are not guided by an evidence base.

Rationale for the study

Yoga is promoted as a safe and effective exercise program, capable of increasing the strength, flexibility, and functional capacity of older & younger adults including those in robust physical condition as well as those with musculoskeletal disorders.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and the National Recreation & Park Association recommend Yoga as a “total-solution” exercise for older adults. The National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases publication Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Across Your Lifespan states that “yoga combines balance, flexibility, and strengthening benefits.”

However, little formal research has been done to study the physical demands, efficacy, and safety of Yoga programs for older adults.

In general, older adults have less joint range of motion, less strength and poorer balance than younger men and women. Seniors generally have more limiting musculoskeletal conditions, such as osteoarthritis and low back conditions that may put seniors at higher risk of musculoskeletal side effects from Yoga.

Our concerns about risks of musculoskeletal side effects from Yoga were also based on results from our prior work, a clinical trial of Yoga for excess thoracic curvature in men and women aged 60-90 years of age. In that study, approximately 60% of the 120 participants in that study developed musculoskeletal soreness and/or pain significant enough to require additional variations of their poses (all “standard” poses had already been modified in an attempt to make them suited to older adults). Further, participants with pre-existing musculoskeletal conditions (even quiescent ones) developed muscular complaints earlier during the intervention than those without pre-existing conditions.

Brief description of biomechanical investigation

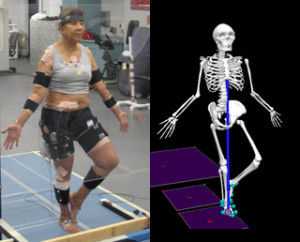

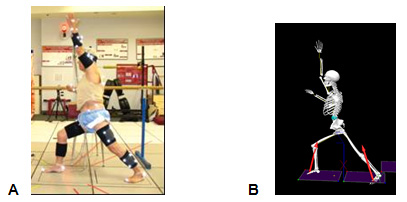

We used biomechanics to capture information about the physical demands placed on the muscles and joints by Yoga, as well as the functional performance adaptations (e.g. strength or balance changes) associated with doing Yoga. Illustrations of how biomechanics measurements are obtained and quantified are shown in Figures 1A and 1B, below.

The physical demands of yoga can be quantified by measuring the joint moments of force (JMOF) generated during the performance of the poses (Figure 1). JMOF are generated by muscle activity and the ligaments that “tie” joints together.

Higher joint moments of force can be beneficial or harmful. Joint moments of force increase muscle loading (the work that the muscle is doing) and therefore may stimulate beneficial adaptations (e.g. build strength & endurance). On the other hand, excessively-high joint moments of force may result in the overloading the joint, which can worsen existing joint pathology (e.g. osteoarthritis). For example, a high medial (valgus, or “inner side of the knee”) joint moment of force can place a strain on the medial collateral ligament. This strain on the ligament increases joint reaction forces across the lateral condyles (bones that are part of the knee joint). This increased force can be damaging to the outer portion of the knee joint

Figure 1A: Senior participant performing a Yoga pose (asana) while instrumented for biomechanicalanalysis.

Figure 1B: Biomechanical model of the same participant, showing the reaction forces measured by the biomechanical instrumentation.

Yoga Poses

Based on our geriatrics, biomechanics and Yoga knowledge, we designed a program of Yoga instruction aimed at strengthening all major muscle groups and improving balance-while avoiding injury. Based on classical Yoga principles, we designed two series of poses, which were taught in sequence. As is customary, each series had a set of opening postures (akin to a “warm up”), a middle sequence (the “intense part of the work out”) and a closing sequence (similar to a “cool down”). Descriptions of the poses and pictures of each are contained on the YESS Series 1 and YESS Series 2pages. Please be advised that these pose descriptions are not intended for use by students who have not participated in our class. We provide them so that the academic and Yoga teaching communities may see what was done in our classes.